February 14, 2022

University of Missouri researchers are closer to deciphering historical scripts that could shed light on life and business in 17th Century Latin America. Mizzou’s Praveen Rao and Viviana Grieco from UM-Kansas City are using machine learning to translate thousands of notary records currently housed in the National Archives in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

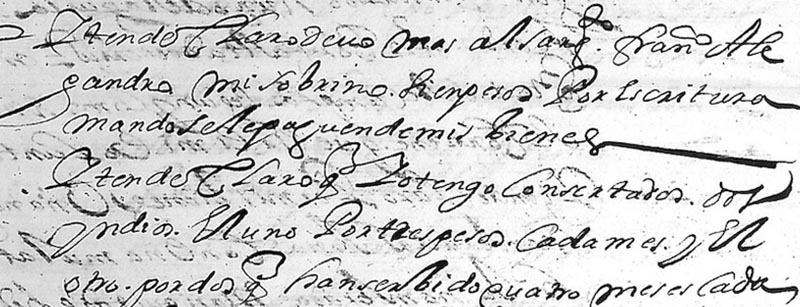

The collection contains some 200,000 deeds, mortgages, wills, dowries, marriage licenses, contracts and other documents. At least 35 different notary publics drafted the records, which are written in an ornate Spanish script illegible to most scholars today.

So far, the researchers have been able to decode about 60,000 records written by one individual notary, said Rao, an associate professor with joint appointments in health management and informatics and electrical engineering and computer science.

“We’ve shown that our proof of concept actually works,” he said. “Now, we need to develop new techniques that will allow us to generalize the detection of words and allow us to translate the other handwriting based on little data.”

To get to this point, the research team has had to overcome numerous challenges, said Grieco, a professor in history and Latin American & Latinx Studies. First, scans of the original documents had to be cleaned of discoloration, ink smudges and other noise.

Then, Grieco’s students, who are trained in paleography, identified and labeled characters and words they could decipher. Rao’s Ph.D. students, Shivika Prasanna (MU) and Nouf Alrasheed (UMKC), retrained open source optical character recognition and object detection tools to enable the machine to detect characters and words in more than 6,000 documents. They are also involved in developing the software tool for the project.

The resulting knowledge graph and retrieval system works like this. A historian can search for a key word such as “donacion” (Spanish for “donation”) just like one might enter a keyword into a search engine. The system then retrieves all records containing that word, with the word highlighted on the image and a footnote showing the page number of the original document.

Users can also provide annotations, meaning they can flag words that the machine might have missed or make corrections if necessary.

“Once the tool is used by many people, they will do the annotation for free and allow us to collect a lot of labels very quickly to retrain the deep learning model,” Rao said. “Users will be involved in making the results even better.”

He also hopes to add a feature that would allow historians to filter their results by types of contracts, time periods and specific places where the document might have been notarized.

A successful collaboration

Last year, they received funding for the work from the National Endowment for the Humanities, which they hope will be continued this year.Rao and Grieco first teamed up on the project at UMKC, where they received seed funding from the campus. Through the UM System’s focus on interdisciplinary collaboration, they were able to continue their partnership when Rao took a position at Mizzou.

The collaboration has proven invaluable, Grieco said.

“I went to Praveen with the problem not knowing the capabilities,” she said. “Now, I can provide input on how things are being developed from the computer science end because I am looking at the collection with completely different eyes. I can think of problems in the collection I’d not thought of in the past.”

The work to date has resulted in a paper published in Digital Humanities Quarterly Journal and a publication in Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Structuring and Understanding of Multimedia Heritage Contents co-located with Association for Computing Machinery Multimedia 2021.

Researchers also provided an update on the project to the National Archives in Argentina, where attendees were excited about future possibilities.

“People who attended from other archives contacted me and asked if it would be possible to come up with something similar for them,” Grieco said. “The project has received a lot of attention because we’ve been able to advance it in the direction we thought it could go. Even though we’re developing a tool for this particular collection, the ways we thought about the problem can help us develop tools for other collections. We think we will be busy with manuscripts in general for a long time.”