September 12, 2021

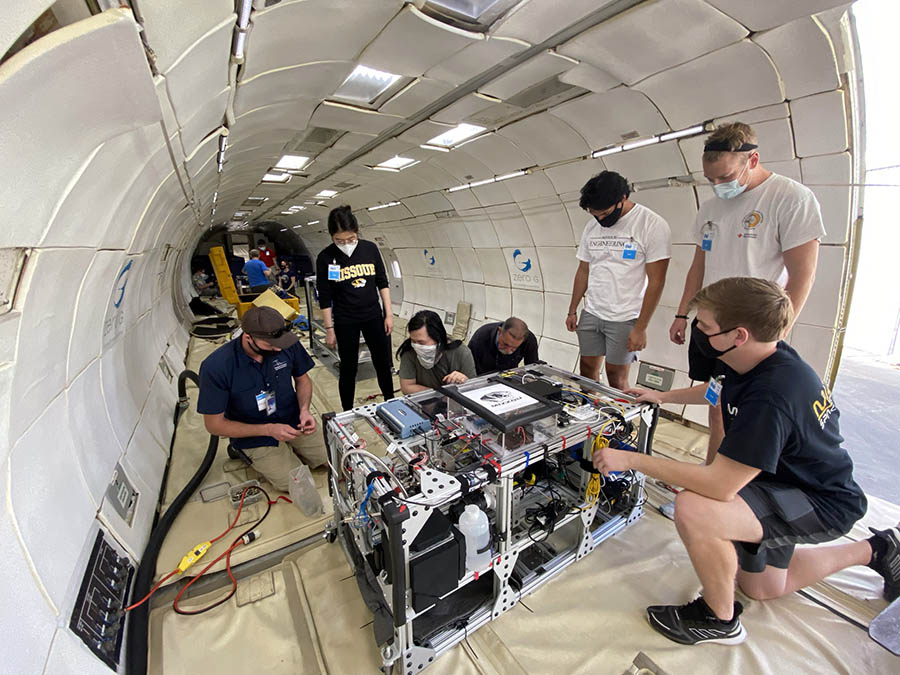

A Mizzou Engineering team is heading back to a zero-gravity environment this semester to continue research around water in space. Professor Chung-Lung “C.L.” Chen received a continuation of grant funding from NASA to send researchers, including undergraduate students, to G-FORCE ONE in Florida.

“The program was supposed to end this spring, but NASA liked our results,” said Chen, who is the William and Nancy Thompson Distinguished Professor in Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering. “We found more intriguing phenomena and mechanisms, so they would like us to explore further.”

Last year, Assistant Research Professor Sheng Wang led the group to G-FORCE ONE, a modified Boeing 727 that takes passengers on parabolic flights replicating gravity-free conditions.

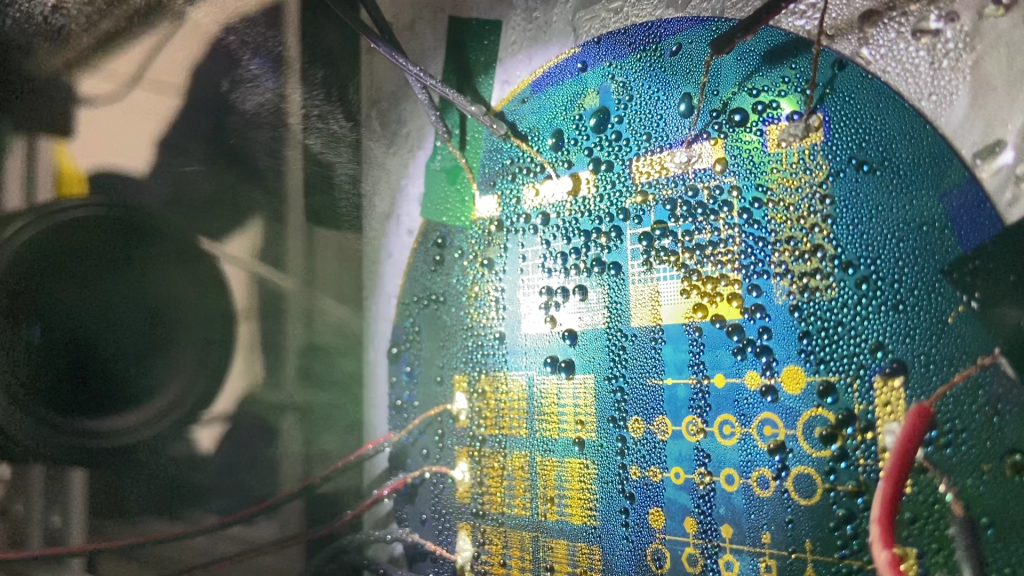

During the trip, the team conducted experiments around electrowetting, a technique that uses electric fields to improve condensation on surface areas. With a device developed in Chen’s lab, the team was able to significantly enhance condensation.

“The most important finding was that without gravitational force, we could see the condensation rate was enhanced during the flight test,” Wang said.

On Earth, condensation forms when heat is transferred and energy is lost with gravity assistance, turning water vapor into liquid. By creating more condensation, this research could lead to effective ways to harvest water on spacecraft such as the International Space Station.

The electrowetting technology also allows better control of water droplet dynamics. Rather than falling downward as they do on earth, water droplets move in different directions via electrowetting without gravity.

“When we use electrowetting to make a specific spot of surface wet, we can become more strategic in time and space with patterned hybrid surface.,” Chen said. “If we know more about fundamental mechanism of condensation dynamics, we can control it and change surface wettability adaptively.”

On board a space station, this would give astronauts control over limited moisture. For instance, they may want droplets close to computational devices or instrumentation to absorb the heat from those electronics, Wang said.

“If we have a hot spot, we can purposely move droplets toward that area because liquid can absorb a lot of heat, allowing us to lower temperature locally,” he said.

The team will further investigate that heat exchanges during the next trip to G-FORCE ONE.

Dropwise condensation on microfabricated devices during a zero gravity flight.

Future work

While the parabolic flight in Florida provides a good testing environment, researchers have just 17 seconds per parabola to work in an nearly gravity-free condition.

“Eventually, we would like a longer duration of zero gravity so we can test in more stable experimental conditions,” Chen said.

That could include partnering with astronauts on board the International Space Station. After all, if humans are to ever inhabit Mars or the moon, they’re going to have to know how to survive in zero-gravity environments.

But the process also has plenty of applications here on Earth, Chen said. It could be used to make blood testing more efficient by controlling the shape and movement of a droplet on a chip, or to create liquid lenses that can follow the sun and collect solar energy.

“There are a lot of applications for this,” Chen said. “If we know more about the fundamental mechanisms of how to control this interface, we can benefit in the near future.”

And just as important, he said, is that the G-FORCE project has piqued the interest of students.

“One objective of the zero-gravity flight is education,” Chen said. “If we are able to get students excited and motivated to do this kind of research, it will be good for the university and good for the country.”