April 03, 2022

As the nation was progressing at the turn of the century — with both rural Americans and millions of immigrants flocking to sprawling urban areas seeking opportunities — so, too, was the College of Engineering finding its identity in the early 1900s.

In his book, “Engineering at the University of Missouri,” Professor Mendell P. Weinbach called this period a “conspicuous” time for the College. On one hand, industry needed engineering curricula that met the technical demands of the profession. At the same time, cultural subjects such as economics, history and social sciences were considered essential areas of study. Attempts to synchronize it required a careful balance, Weinbach wrote.

In 1910, College administrators tried to address conflicting interests by swapping its four-year degree for a five-year program. Entrance into engineering studies required two years of arts and sciences with the last three years devoted to technical training. The degree was changed from that of a BS to professional designations, CE, ME, EE and ChE.

The results were dismal. Enrollment plummeted from 411 students in 1910-1911 to 145 students by 1913. By the start of the 1915 academic year, the College had returned to the four-year program with an optional fifth year for a professional degree. Enrollment immediately bounced back.

During those years, however, the College managed to develop coursework that aligned with the progress happening across the country, bringing in industry experts to help. Civil engineering now included A. Lincoln Hyde, a graduate of Yale who spent several years working for national bridge builders. Hyde introduced the first organized course in structures, a fundamental topic in bridge engineering.

The growing expansion of electrification in America ushered in studies around high-voltage transmission of power. Edward K. Kellogg, who had previously served on the research staff of RCA (Radio Corporation of America), introduced the first comprehensive course in telephone communications in 1912. Mechanical engineering also evolved with coursework around thermodynamics, internal combustion engines and, later, refrigeration.

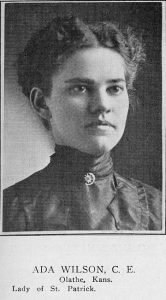

The College’s social landscape was progressing, as well. In 1906, the Missouri Shamrock debuted as a small pamphlet to commemorate Engineers’ Week. A year later, it returned as a 55-page book that highlighted the lighter side of the student body. Dedicated to “those who have succeeded in making the name of ‘Missouri Engineer’ stand for the height of excellence and ability,” the Shamrock included drawings, poems, songs, jokes and short student profiles.

Among those featured in the Shamrock that year was Ada Wilson, who became the first female graduate of the College in 1907 — 13 years before women had the right to vote. The Shamrock describes “few hearts like hers,” and states, “If there’s another world, she’ll live in bliss; if there is none, she will have made the best of this.” Equipped with a degree in civil engineering, Wilson went on to run her family’s business, Wilsonia Dairy, until it closed in 1946. She died in 1967. Mizzou Engineering continues to recognize her contributions each year during the Ada Wilson Green Tea Lecture named in her honor.

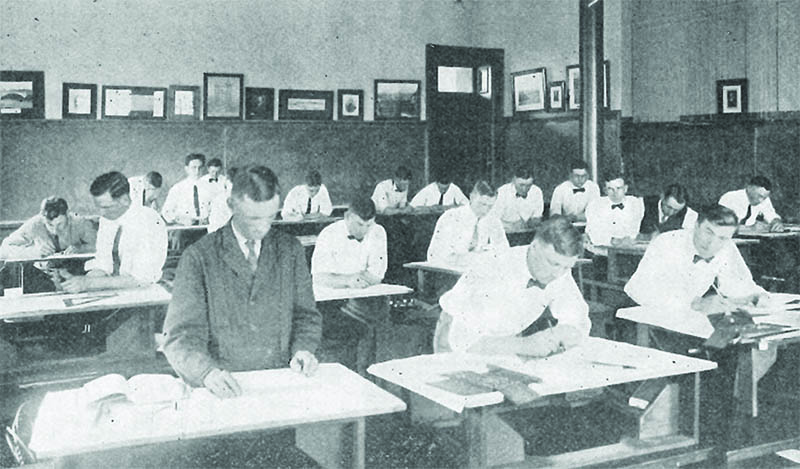

The early 1900s also saw the establishment of the Engineering Library, which opened in 1906 to provide engineering-specific resources to students and faculty. By the middle of the century, Weinbach described it as one of the best-equipped engineering libraries in the Midwest with more than 15,000 technical books, reference materials and periodicals published in the U.S. and abroad. Over the years, the engineering library has served as a central hub for students to gather, study and collaborate.

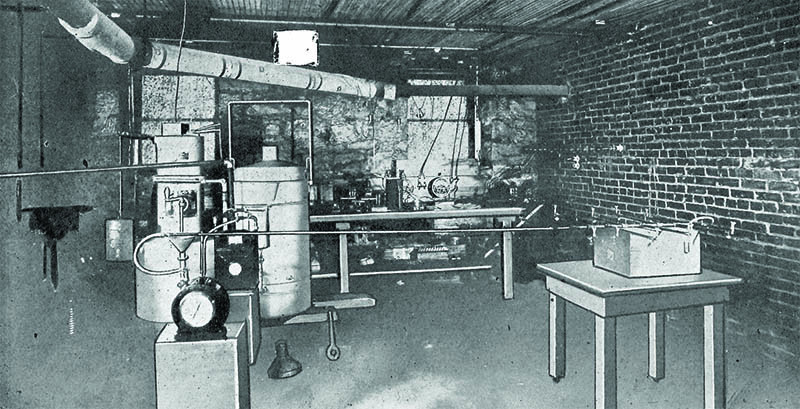

In 1909, the College and Dean H.B. Shaw established the Engineering Experiment Station as a center for research. Results of experiments were published in the “Bulletin of the Engineering Experiment Station,” which covered topics such as road materials, distribution of electrical energy, chemical and physical properties and water resources and supplies. Activities at the station would flourish for decades, interrupted only by the Great Depression and World War II.

This is part of a year-long series around the history of Mizzou Engineering. Read about previous decades here.