May 10, 2022

Mizzou Engineering — like the rest of the country — was feeling the impact of world war in 1917. That year, an essay in the Missouri Shamrock, engineering students’ annual publication, noted that European wars had necessitated the manufacturing of firearms, which was beginning to control financial markets. The following year, World War I had become more personal. The yearbook listed four pages of names of Mizzou Engineering students and alumni who “answered the call” and enlisted. The following year, the Shamrock was dedicated to nine Mizzou Engineers who died in service to their country. Among the dead were two who succumbed to the 1918 influenza pandemic that ravaged much of the globe and temporarily closed universities across the country, including Mizzou.

One essay in the 1918 Shamrock questioned whether engineering professionals would best be of service by strategizing military warfare tactics off the battlefield, such as finding more efficient ways to transport fish to troops during meat shortages and increasing the production of corn. The thinking aligned with popular messaging of the time promoting rationing and declaring food as ammunition.

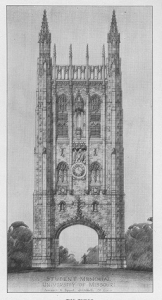

By the 1920s the College entered another period of growth, as did the campus as a whole. In 1922, design began on a new building, Memorial Union, known at the time as Memorial Tower. The structure, in the architectural style of English Gothic, was built by Mizzou Engineering alumnus B.D. Simon. Names of students who lost their lives in the war are engraved on the north and south walls, where they continue to be honored today.

The 1920s also saw rise to more alumni and student activity. Professor Mendell Weinbach’s early chronology of Mizzou Engineering notes that a loyal alumni group was established in Chicago in 1925 — six years before the Engineering Alumni Foundation would be organized. The Chicago group established an engineering scholarship given to the highest-ranking junior in the College who also participated in extracurricular activities.

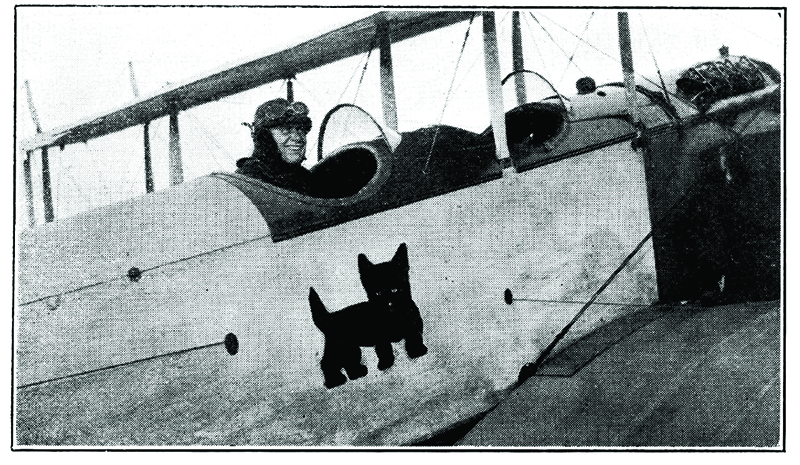

And there were several ways to get involved outside of classes at this time. The rapid progress of the profession in the early part of the century had led to the creation of national engineering professional groups including the American Society of Civil Engineers, American Society of Mechanical Engineers, American Institute of Electrical Engineers and American Institute of Chemical Engineers. The College followed suit, establishing student chapters of AIEE and AIME, as well as Tau Beta Pi, the honorary engineering fraternity. The St. Pat’s Board was also active at this time and expanded St. Patrick’s Day festivities to a full week of activities in 1921. Festivities started to include the crowning of a St. Pat’s queen and addition of more honorary knights—including future President Harry S. Truman, who would be knighted in 1934 as he sought his first term in the U.S. Senate.

The Mizzou Engineering Library also flourished during this period under the leadership of Mrs. Jane A. Hurty. In 1917, the Missouri Shamrock is dedicated to her for taking “every interest in the affairs of Saint Patrick and his followers.” Hurty oversaw library operations from 1913 to 1938.

As so-called candlestick telephones — the vertical phones with separate mouthpieces and receivers — were becoming more commonplace in American homes, Mizzou Engineers were working on emerging technologies in telecommunications. In 1929, the College established a well-equipped laboratory with support from the American Telephone and Telegraph Company and its associate, the Southwestern Bell Telephone Company. The equipment comprised of valuable apparatus for the study of circuit behavior.

Research and educational activities would come to a screeching halt over the next few years as the effects of the Great Depression swept through America. Between 1931 and 1934, enrollment in the College of Engineering dropped by half. Teaching staff was gutted. Engineering buildings and lab equipment deteriorated because of the lack of maintenance. The Engineering Experiment Station was essentially dormant.

Students were feeling it too, although administrators and editors of the Shamrock tried to remain positive. In 1931, Dean E. J. McCaustland wrote that despite the industrial depression, enrollment was normal. The following year, he acknowledged that attendance had fallen and that graduates were having a tough time finding employment. A 1931 editorial in the Shamrock urged students to broaden their studies outside of engineering to make them more employable.

Perhaps to make a case for enrollment, the 1933 Shamrock reminded readers of the loftier goals of collegiate study and praised “those who are to follow in the realization that education is not concerned with accomplishment but is an aid toward the harmonious expansion of human nature.”

By 1934, federal emergency relief grants, including allocations for public buildings, helped to turn the tide. It was during this period that great civil engineering feats including the Hoover Dam, the Golden Gate Bridge and the Empire State Building were built, creating more engineering jobs. On the MU campus, grants contributed to the construction of a dozen new buildings including a new engineering facility for research laboratories. The Engineering Laboratories Building injected new life into the College, Weinbach wrote, and restored enthusiasm among faculty.

The facility was built during the first year of the administration of F. Ellis Johnson, whom Weinbach credits with substantially increasing student attendance. Johnson also raised the standard of admission and increased requirements for graduation. All courses of study offered by civil, mechanical and electrical engineering became officially approved by the Engineering Council for Professional Development. Johnson’s tenure would end in 1938 when he left for position in Wisconsin.

This is part of a year-long series around the history of Mizzou Engineering. Read about previous decades here.