June 09, 2022

Our series on the history of the College picks up in the mid-1930s when the country is still grappling with the ramifications of the Great Depression. At Mizzou Engineering, this is evident by low enrollment and significant budget cuts, resulting in fewer faculty. While the national economy improved in 1938, bringing with it a spike in new students, it would take another two years for the College’s budget to rebound — if only temporarily.

Despite economic hardships, Mizzou Engineers were staying ahead of emerging technology of the times. Radios had become popularized through President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Fireside Chats, a series of evening broadcasts that began in 1933. At Mizzou, “Radio Communication” was added to electrical engineering curriculum in 1935, covering principles underlying the generation of electromagnetic waves, broadcasting and receiving circuits, and antenna design systems.

Additionally, Mizzou Engineering researchers were studying oil refining; looking at ways to improve Missouri’s secondary roads as more highways, such as U.S. Highway 66, were being built across the state; and determining how the Bagnall Dam was impacting both river flow and the generation of power at Union Electric Light and Power Company.

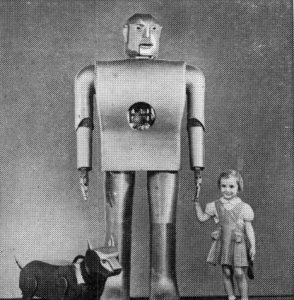

In the early 1940s, research included railroad signaling from centralized traffic control, fluorescent lighting and the biproducts of coal. And in 1942, Mizzou Engineers were intrigued by technology coming from Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company. In the 1942 Shamrock, students marveled at Westinghouse’s mechanical man and dog, which had debuted at the 1939 World’s Fair. “Electro” the motorman was deemed a “smart” fellow, as he could respond to instructions given to him via telephone, tasks such as talking, walking and counting.

Just as its predecessor two decades earlier, World War II took a heavy toll on the College as staff members and students left for the armed forces and impacted industries. Regular enrollment dropped from 700 in 1942 to 100 in 1944. Graduate assistants decreased from 28 to two. Just eight faculty were left.

But it also provided an opportunity for Mizzou Engineering to expand its reach by training women to be radio technicians in a “Pre-Service Training Course.” Overseen by the federal government, participants were considered government employees and had to be in class 48 hours per week to meet employment requirements. Enrollees took courses such as “Principles of Electricity,” “Materials,” “Antenna and Wave Propagation,” and “Radio Laboratory.” After completing the course, women were sent to Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, to assist with research, development and test projects for airborne radio equipment.

The war would continue to impact the College even after it ended in Europe. Of some 20 faculty members who left to fight, just half returned to resume teaching. Meanwhile, enrollment would explode to more than 1350 by 1946 when students who enlisted returned.

“Class conditions in the College of Engineering and elsewhere in the University will not be ideal this fall,” Dean Harry Curtis reported in October of that year. In the coming years, he’d get creative about finding solutions.

This is part of an ongoing series exploring the history of Mizzou Engineering. See previous decades here.