August 09, 2022

Our series exploring the history of Mizzou Engineering continues in the year 1968, when William Kimel begins what would become a 17-year tenure as Dean of the College. Kimel became known for his collaborative style and had a keen interest in developing bioengineering studies in partnership with the School of Medicine. Bioengineering courses and research activities would be primarily under electrical engineering in the 1970s until the subject became a formal program in 1980.

Perhaps the biggest impact on the future of Mizzou Engineering was Kimel’s foresight. He understood that the application of emerging technologies would propel engineering into physical, behavioral, social, medical and communication sciences.

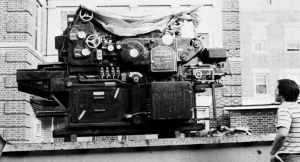

Across the country, a technological revolution was underway. Western Electric launched a “Picturephone,” which transmitted images over wires. Early fax machines were transmitting full-sized newspaper pages at a rate of six minutes per page. Computers — incorporated into Mizzou Engineering curriculum in the 1950s — were becoming fully integrated in industry.

Among the inventions changing the landscape of society was the pocket calculator, which emerged onto the scene in 1972. This handheld device would replace the beloved slide rule, a calculating device that had been an engineering essential and seen as a symbol of the profession for decades.

A 1978 editorial in the Missouri Shamrock used the example to showcase just how quickly society was changing. In the article, John Lewis wrote about how he had recently visited his father, a veteran engineer.

“When I walked in his office, he was working on a problem using his old favorite slide rule, instead of his new programmable calculator,” Lewis wrote. “When I asked him why, he tried to explain that there was a certain magic and mystery in using a slide-rule, it was an art, any fool could use a calculator. A true artist uses a slip-stick.”

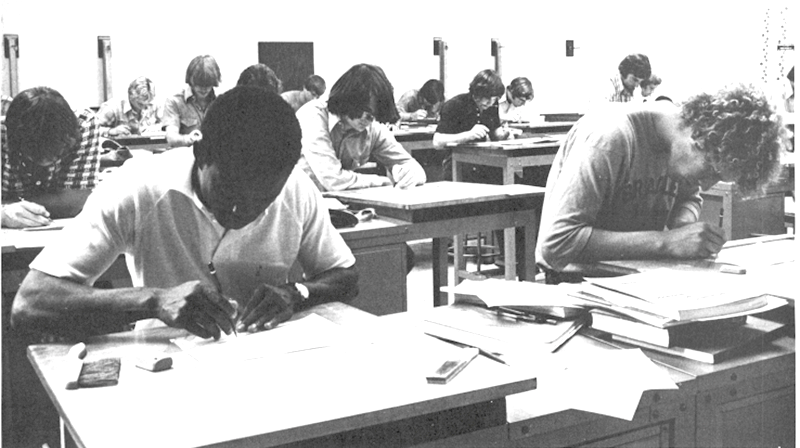

Lewis goes on to outline other advances over the past two decades: nuclear engineering, space stations and efforts to colonize the moon. He also noted the changing demographics of engineering, with more women and minority students entering the field.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if someday while I’m in my office working a problem on my calculator when my son, or daughter will ask me why I’m using an outmoded instrument,” Lewis wrote. “I’ll try to explain about the art and mystery associated with a calculator.”

At the same time engineering was transforming alongside these new technologies, a cloud was hanging over the industry. In the late 1960s and early 70s, the national reputation of engineering as a profession hit a low point — some historical accounts blame the weapons used in the Vietnam War for public perceptions. Mizzou Engineers were feeling the pressure.

A 1968 Shamrock editorial urged engineers to “stand up for your professionalism, lest it be swept away by the tide of public belief. Our professional status, as engineers, is at stake.”

The article goes on to say, “No other profession touches upon public life and influences the public welfare more than that of engineering. With a society as dependent on technology as ours, engineering and engineers play an ever-increasing role in the public welfare. At the same time, engineering as a profession rather than a trade becomes essential to the present and future welfare of the society.”

On campus, the College, under Dean Kimel’s leadership, was also navigating political winds. In 1972, under direction from Missouri lawmakers, the UM System launched an initiative known as Role and Scope. It required schools and colleges across the four-campus system to essentially justify their existence with the goal of reducing redundant programs and inefficiencies. It’s clear from the Missouri Shamrock, that engineering students were not a fan of this undertaking.

But the initiative might have ultimately played a role in helping define Mizzou Engineering’s unique identity. To differentiate the program during the Role and Scope process, administrators focused on the interdisciplinary nature of the curriculum. At Mizzou, engineering students could combine their scientific studies with other fields such as medicine, business and agriculture to customize their education and become leaders in specialized areas. That cross-campus collaboration continues to set the College apart today.

It was also on Kimel’s watch that the College began efforts to renovate the Engineering Building. After a few unsuccessful fundraising attempts, James E. “Bud” Moulder, MS CiE ’53, who was active in the MU Engineering Alumni Organization, took the cause to state representatives, who formed a committee to study the request. In 1978, $1.87 million in funding for renovations was approved. Construction work would begin two years later on the building we now know as Lafferre Hall.

This is part of an ongoing series on the history of Mizzou Engineering. Read more here.