December 06, 2022

By Eric Stann | MU News Bureau

While heart disease is a leading cause of death in the United States, most people can be treated with early detection and timely interventions. That’s why Zheng Yan and a team of researchers at the University of Missouri are using a $2.6 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to help create a breathable material — with antibacterial and antiviral properties — to support the team’s ongoing development of a multifunctional, wearable heart monitor.

The wearable device is designed to continuously track the health of a human heart via dual signals simultaneously — an electrocardiogram (ECG), which measures a heart’s electrical signal, and a seismocardiogram (SCG), which measures heart vibrations. After these signals are recorded on an electronic device, this information could be shared with a person’s healthcare provider to help identify potential warning signs related to heart disease.

Yan, an assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical, Biological and Chemical Engineering and the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, said the device is designed for use in personalized health care.

“We want to provide comprehensive information about the status of a person’s heart,” Yan said. “Effects of heart disease can often happen unexpectedly, so it’s important to have continuous, long-term monitoring for early detection and timely interventions. We want this to help reduce the number of people succumbing to death from heart disease in the U.S.”

Since the breathable material encompasses the device and may potentially stay attached to a person’s skin for at least a couple weeks, or even up to one month, Yan said the material’s integrated antibacterial and antiviral properties can help prevent the accumulation of harmful bacteria and viruses from forming on the surface of a person’s skin underneath the device itself.

The material’s breathability is also designed to help mitigate the loss of an accurate signal when a person sweats. Another benefit is the material’s ultra-soft properties, Yan said.

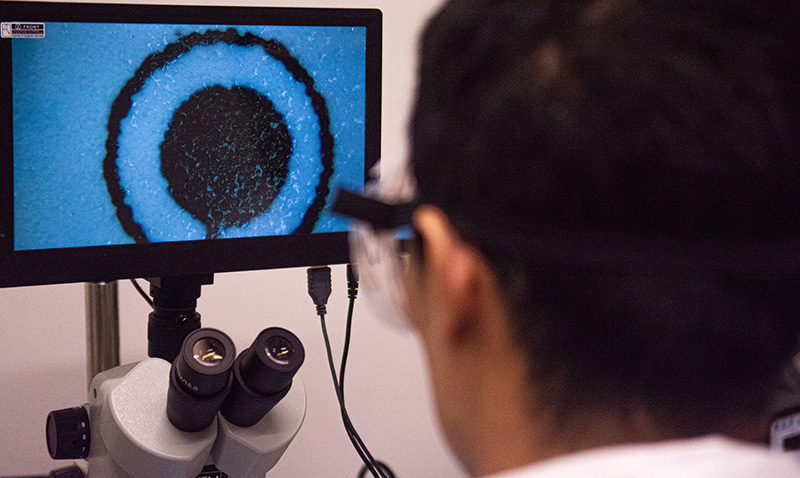

“Under the microscope, our skin is not flat,” Yan said. “So, an ultra-soft material can form what we call a conformal contact, which is very important for us in order to have a high level of accuracy for our signal recording of the electrical activity of the human heart.”

Similar devices in existence today typically only monitor the human heart via an ECG, and have limited long-term use, Yan said. Currently the device is a small, wired patch connected to a small data processor that can be attached to a person’s shirt, and researchers hope to one day develop a wireless version.

The project, “Multifunctional Porous Soft Materials for User-Friendly Skin-Interfaced Bimodal Cardiac Patches with Long-Term Biocompatibility and Antimicrobial Property” is being supported by the National Institutes of Health (1-R01-EB033371-01).

Collaborate with peers to engineer next-generation medical devices. Apply today!