October 23, 2022

A University of Missouri research team has proved that a machine can be trained to decipher centuries-old scripts. Now, they want to see if that model is smart enough to read other handwritten documents from the era without as much human assistance.

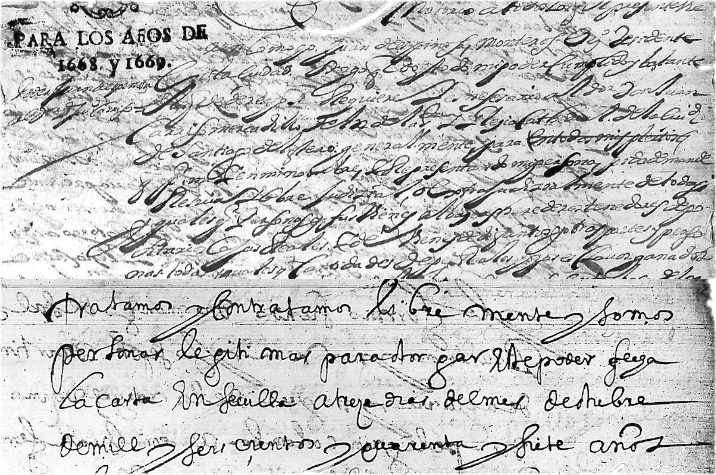

At issue is a collection of 200,000 handwritten notary records from 17th Century Argentina. The deeds, mortgages, marriage licenses and other documents are written in Spanish, but in an ornate script not legible to most historians.

Mizzou Engineering’s Praveen Rao and Viviana Grieco from UM-Kansas City have been working on translating the documents using machine learning for the past several years. They recently received a second round of funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities for the work.

Grieco is a professor in history and Latin American and Latinx Studies and is a trained paleographist. She approached Rao several years ago about coming up with a process to digitize the collection, which is housed at the National Archives in Argentina.

“We want to make these records accessible to those who don’t have specialized training,” she said.

For the first two phases of the project, Greico’s students spent months manually identifying and labeling specific words from scanned images of documents written by a single notary.

Rao’s graduate students then used that data and open source optical character recognition to train a machine to recognize those words throughout that particular set of documents.

For the most part, that notary’s work has been translated into a knowledge graph and a fast document retrieval system. A historian can search for a specific word, then the model highlights and retrieves all records containing the word. Users can also flag any words that the machine might have missed, which will continue to improve the results.

While that process worked well, a more efficient method is needed to decipher the rest of the collection — which includes records written by more than 20 different notaries.

“We used the best possible approach, but we cannot duplicate that effort for every hand in the collection,” Grieco said. “We proved the concept, now we need to simplify the process to get the same results.”

To do that, Rao and his students are using an upcoming area of machine learning known as few-shot learning, which requires less training data. Further, they plan to scale the system to manage the entire collection.

Grieco’s team will manually translate a few examples from different documents to see how well the machine can find those words throughout the collection.

“The more data you provide, the better a deep learning model performs, but sometimes it’s hard to get a lot of labeled data,” Rao said. “Few shot learning is a technique we can use to detect writing of notaries without having to provide too much training data.”

Eventually, Rao would like to develop an even more robust system that provides context.

“Right now, it’s all words,” he said. “Once we have the basic components, we can go into more advanced natural language processing techniques. That’s our next focus — applying more advanced technology to understanding the meaning of sentences so that Viviana and other historians can ask a question and the system can answer that from the documents.”

That possibility is ambitious and exciting, Grieco said.

“For me, just being able to find keywords and types of deeds in the collection is a really amazing step, but then building upon that and digging into the big data to search for complex answers — that will elevate the collection to a new level,” she said. “We would be able to answer research questions we cannot even consider at this point.”

Read more about the project here. See the knowledge graph here.