November 16, 2025

A careful examination of nursing practices opens up opportunities to improve more lives through data-informed systems thinking.

At Mizzou Engineering, we cultivate knowledge to benefit communities across Missouri and commit to sharing it to improve lives around the world.

Anew study published in Applied Ergonomics reveals how the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted care in an intensive care unit (ICU). Authored by Mizzou Engineering researchers, it highlights the need for dynamic strategies to support nurses and patient outcomes, especially during crises.

In early 2020, Jung Hyup Kim, associate professor in the Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering, secured funding from the National Institutes of Health to study registered nurses’ activity in the ICU of MU Health Care’s University Hospital.

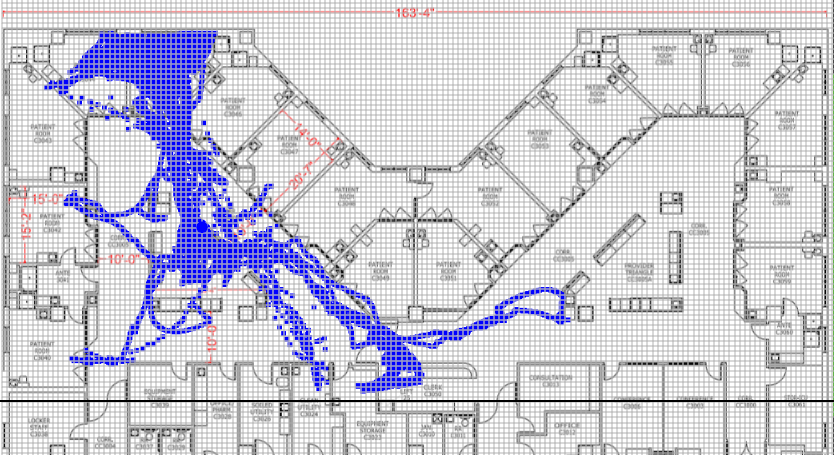

Because of the critical nature of the ICU environment, and to protect patient privacy, Kim and his fellow researchers planned to use near field electromagnetic ranging (NFER), which functions like an indoor GPS, to track nurses’ movements. With this data, they could then find ways to optimize workflows.

The team had just begun the two-month pilot study when a nationwide emergency was declared over the COVID-19 pandemic. University Hospital adopted policies to slow disease transmission, and Kim’s research was suspended.

The team returned to the hospital in July 2020. Working under strict COVID protocols, they began collecting their second month of data. The pause gave them the perfect opportunity for a before-and-after comparison.

What they found was striking: Patient assessment and care time had decreased nearly 50%, while time spent moving patients, fetching supplies and cleaning equipment increased significantly.

“Nurses’ work became much more complex,” Kim said. “Because of pandemic protocols, they had to spend more time cleaning, putting on protective gear and social distancing. All this reduced the time they could spend directly caring for their patients.”

In addition to the NFER data, the team also looked at patients’ sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) scores, which measure illness severity. Typically, the higher the SOFA score, the more time nurses spend caring for the patient. But that correlation weakened post-pandemic.

“Despite their best efforts, nurses couldn’t allocate time based on patient needs as effectively as before,” Kim said.

The study suggests that fixed nurse-patient ratios based on historical data did not function as well under pandemic conditions.

“Dynamic staffing models, informed by real-time tracking, could revolutionize health care delivery,” Kim said

Kim’s work also shows how an industrial or system engineer’s system-level perspective can complement health care professionals’ focus on individual patient care.

“We engineers analyze workflows, identify inefficiencies and seek to optimize processes,” Kim said. “Of course, a hospital is not a factory, where materials flow predictably through stages. In health care, the presence of variability is not just common — it’s the standard, with numerous factors influencing patient care and outcomes at every turn.”

Kim expressed gratitude for MU Health Care’s support of the research, another example of the interdisciplinary collaboration that is a Mizzou hallmark.

“I hope our work can support the University Hospital nurses, who deliver professional, compassion care even under the most difficult circumstances,” Kim said. “They’re the real heroes here.”

Discover more ways our researchers are engineering innovation.